AI approaches can aid subjective tasks in Histopathology

Introduction

Pathology is an important field in medical research and treatment. Physicians often think of pathologic reports as definite diagnoses. However, the pathologic evaluation usually suffers from inter-observer variation. This variation can be attributed to different factors, including the experience of the pathologist, the subjectivity of the task, and the technicalities of immunohistochemical and molecular tests. Among these factors, subjectivity is the one that is possibly handled by using computer vision (CV) models. Such frameworks can be flexibly designed to “quantify” the subjective tasks. It is easier said than done. Quantification of the subjectivity depends tremendously on the task at hand. It can be very different from task to task.

The type of task such as classification and/or segmentation The architecture of the model The entire pipeline from the model’s task to post-model algorithms In this mini-review, I would like to summarize subjective tasks in pathology that require the help of AI, especially deep learning models. There are many subjective tasks in Histopathology, including:

- Disease detection

- Histologic Grading

- Biomarker quantification

Disease detection

Histopathological diagnosis is sometimes subjective under the light microscope. The AI improves and, sometimes, outperforms the accuracy of human pathologists in detecting many diseases, including tuberculosis [1], atherosclerosis [2], prostate cancer [3], lung cancer, colon cancer [4], and so on.

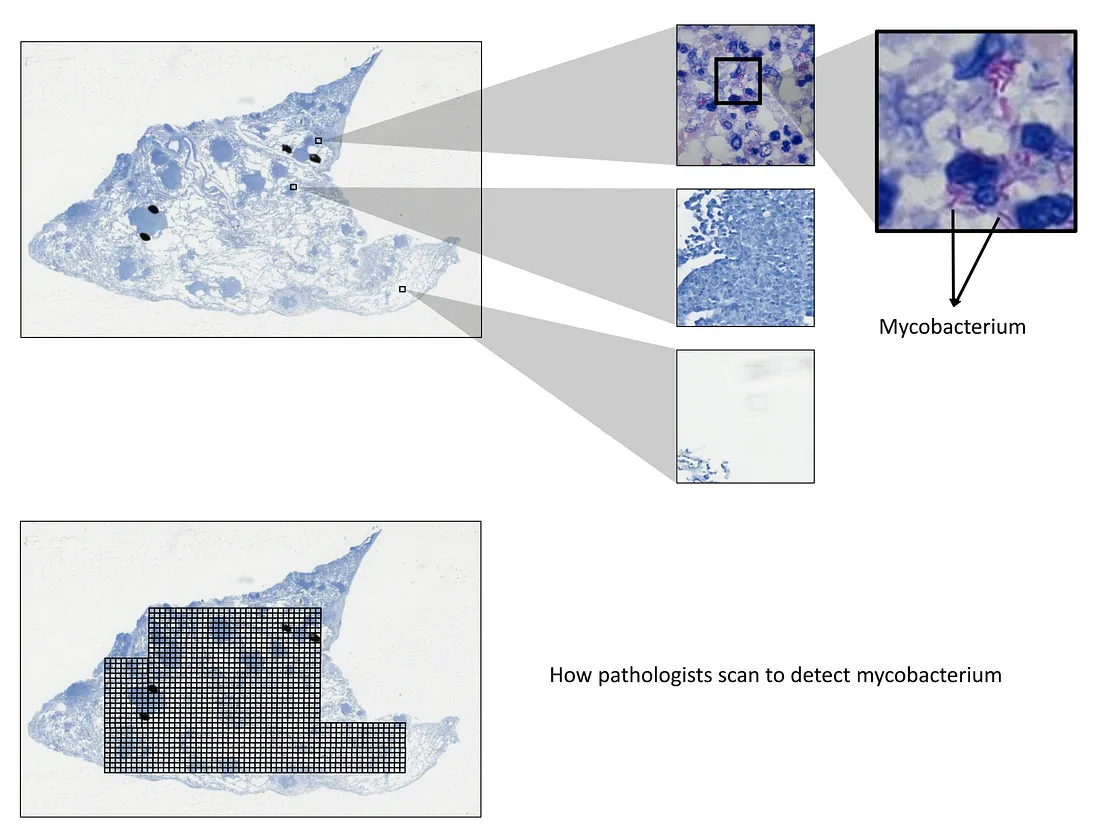

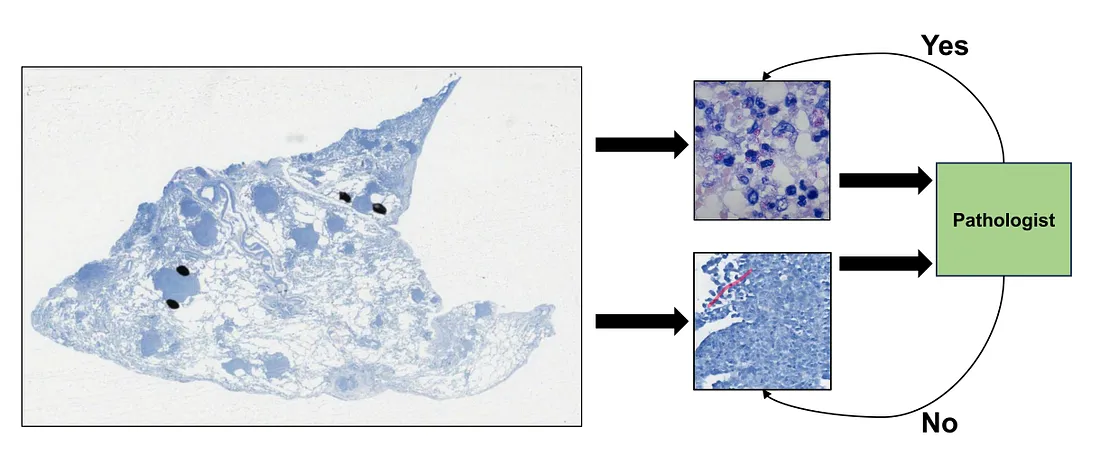

For example, the task of detecting mycobacterium, the bacteria of tuberculosis, under the Ziehl-Neelsen stain can be tedious and exhaustive for human pathologists. This is because the bacteria is so small that it needs to be observed under the highest magnification.

Technically, pathologists have to scan each visual field under this magnification, which leads to too long scanning time. Therefore, we will need an AI that can detect the mycobacterium with high sensitivity, meaning that it can include both mycobacterium and non-specific details as long as it can bring these details up to the pathologist’s attention. This system makes sure no findings are missed out, and, in the meantime, reduces the workload of pathologists. Another point is that the training of this system is affordable because the detection task is simple.

Histologic grading

AI system has a potential to support the human pathologist in histologic grading of different diseases, including non-cancerous and cancerous. I list a few examples of this task:

- Prognostication of morphology [4]. The visual information of histopathology itself can be used to prognosticate diseases such as colorectal cancer. The task can be the classification of “favorable” and “unfavorable” prognoses or to predict the continuous risk of patients, depending on how we design the model and training pipeline.

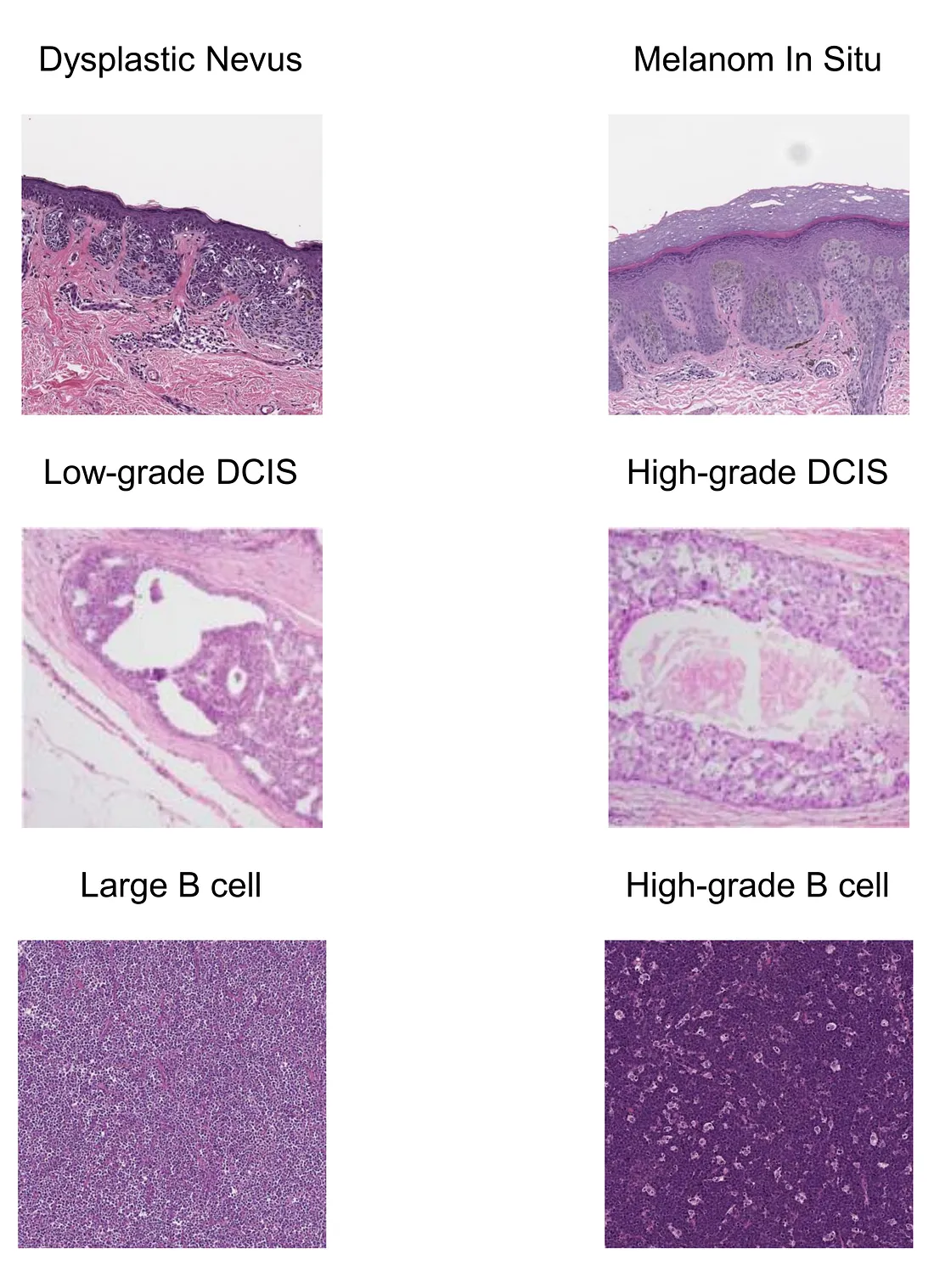

- Melanoma and nevus [5]. Melanoma and nevus are sometimes difficult to distinguish, which is a source of inter-observer variation. Training a model to objectively tackle this diagnostic dilemma can aid the dermatopathological practice.

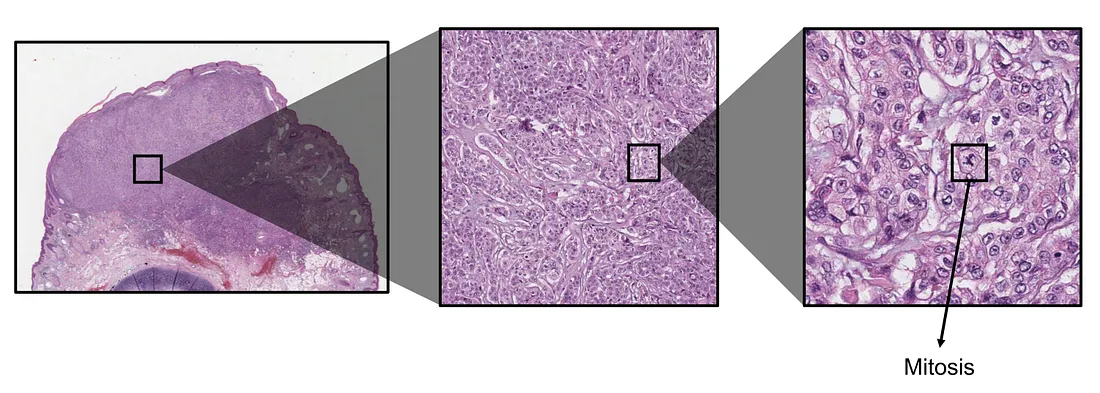

- Breast carcinoma [6]. Mitotic count, nuclear pleomorphism, and tubular formation are the main components to grade breast carcinoma. Grading or scoring these 3 features can be performed by CV models. The resulting scores can be integrated and used for overall histologic grading of breast carcinoma.

- High-grade B cell lymphoma morphology. According to the new version (5th edition) of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematolymphoid tumors, the distinction between large B-cell lymphoma and high-grade B-cell lymphoma is based on the absence or presence of the “high-grade B cell” morphology, which, in turn, depends on the subjective assessment of the human pathologists. To my knowledge, there are ongoing studies to train a good model for resolving this problem.

Biomarker quantification

There are many biomarkers that can be extracted from the WSI of Hematoxyline and Eosin(HE) and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining.

HE-based biomarkers include:

Mitosis. Mitosis is one of the most well-known biomarkers in histopathology, which shows the level of proliferation of cancerous cells. The higher mitosis indicates the more intensive cell division, implicating higher aggressiveness of cancer. Mitotic rate is usually counted by averaging the number of mitoses within a high-power field or squared millimeter. The obvious AI solution for evaluating mitosis is object detection, where the CV model seeks mitosis and counts all mitoses in the tumor region. The total mitosis number is then averaged by the area of the tumor. The mitotic rate counted by the AI approach is, therefore, theoretically more global than human pathologists.

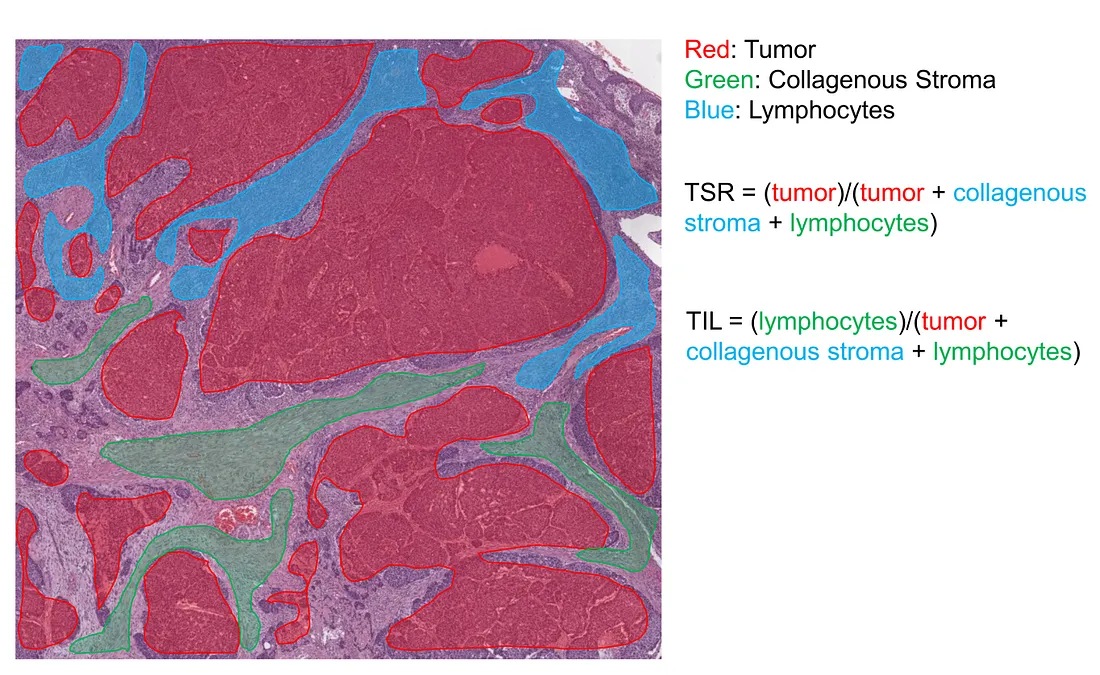

Tumor-stroma ratio (TSR). In recent years, the tumor microenvironment (TME) has been shown to be an important contributor to tumor development. A crucial component of TME, the tumor-related stroma, is of the pathologist’s interest. TSR is the metric that measures the percentage of tumor cells within the stroma, which is subjectively estimated by the human eye, without any measurement device, under the light microscope. The AI solution for the TSR problem is the segmentation task, where the CV model semantically segments the histopathological image into at least tumor and stroma classes. The AI-based TSR is then calculated by the percentage of tumor-related pixels within the stroma-related pixels.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL). TIL is also another crucial component of TME. Higher TIL is associated with “hot” TME, where a more intensive inflammatory response takes place. TIL is also subjectively approximated by the human eye. The AI solution for the TSR problem is the segmentation task, where the CV model semantically segments the histopathological image into at least tumor, TIL, and collagenous stroma classes. In theory, we can combine the TSR and TIL tasks together. However, it is sometimes challenging, depending on the performance of the CV model.

IHC-based markers consist of:

-

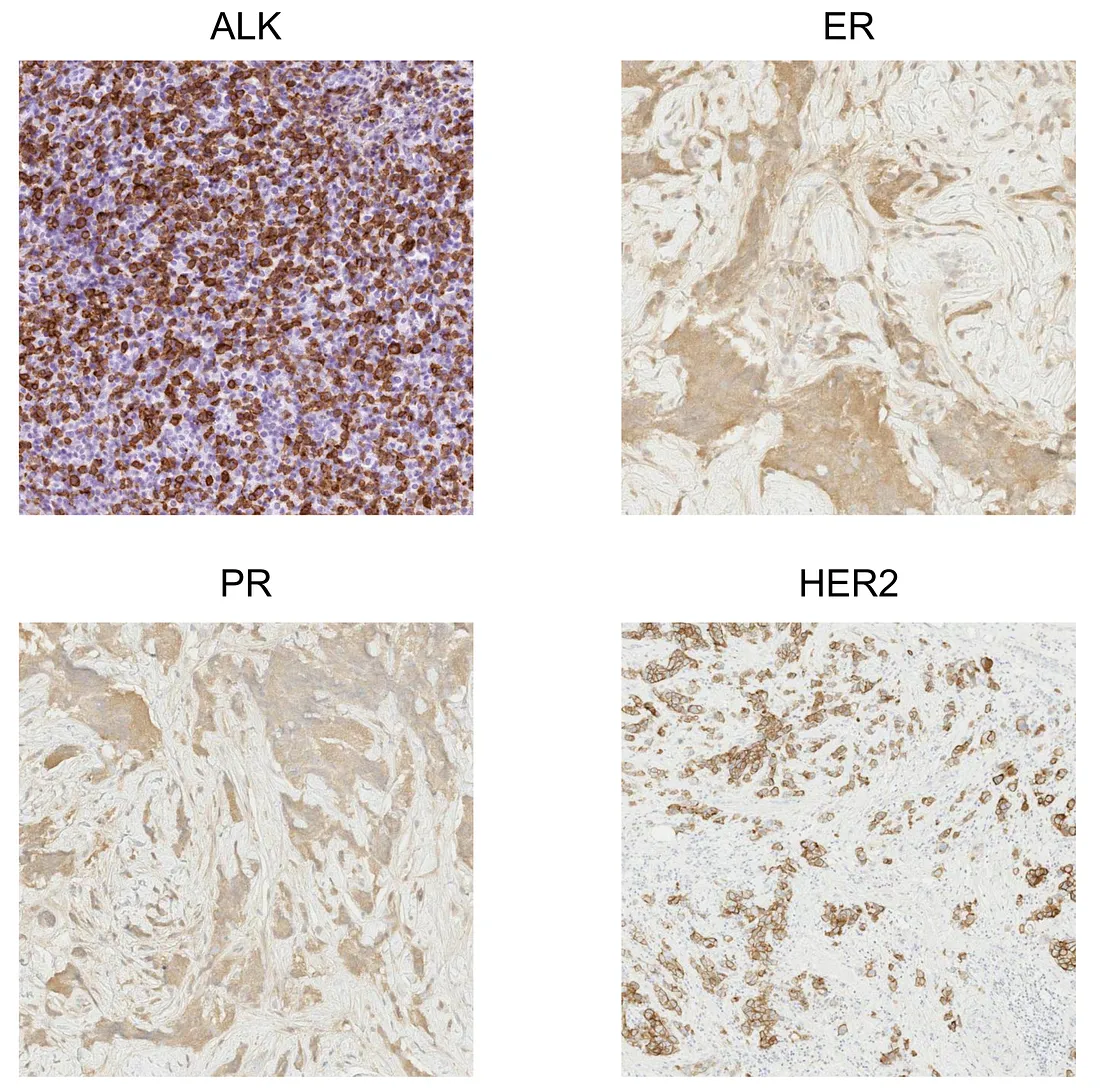

HER2, PR, ER. These 3 IHC markers are very important in the evaluation of breast cancer. They are required in the routine pathological report for planning the treatment modalities.

-

PD-L1. This protein is encoded by the cancer cells in order to protect themselves from the attack of T cells. Immunotherapy is used to inhibit this “immune evasion” process. Therefore, the intensity of PD-L1 expression is very important in monitoring and predicting the cancer’s response to immunotherapy.

-

ALK. This protein is part of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) superfamily, whose function is to activate the signals of cell proliferation. Increased expression of ALK protein indicates higher activity in the proliferation of cancer cells.

-

EGFR. EGFR is a receptor that belongs to the RTK superfamily, whose function is to activate the signals of cell proliferation. Increased expression of EGFR protein indicates higher activity in the proliferation of cancer cells.

Similarly, the AI solution is to train a CV model to segment at least stained tumor cells and unstained tumor cells. Depending on the histopathologic patterns, more classes are possibly required for a more precise quantification. If the model is well-trained, it will be the objective method to quantify the expression of protein-of-interest, providing accuracy and flexibility to evaluate the treatment response.

Conclusion

The subjectivity of pathological quantification problems can be resolved by using AI frameworks. However, designing the training pipeline and calculation algorithms is required to flexibly solve each specific problem.

To those who may be interested, I hope you enjoy this mini-review.

Reference

- Xiong Y, Ba X, Hou A, Zhang K, Chen L, Li T. Automatic detection of mycobacterium tuberculosis using artificial intelligence. J Thorac Dis. 2018 Mar;10(3):1936–1940. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.01.91. PMID: 29707349; PMCID: PMC5906344.

- Holmberg O, Lenz T, Koch V, Alyagoob A, Utsch L, Rank A, Sabic E, Seguchi M, Xhepa E, Kufner S, Cassese S, Kastrati A, Marr C, Joner M, Nicol P. Histopathology-Based Deep-Learning Predicts Atherosclerotic Lesions in Intravascular Imaging. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Dec 14;8:779807. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.779807. PMID: 34970608; PMCID: PMC8713728.

- Oszwald A, Wasinger G, Pradere B, Shariat SF, Compérat EM. Artificial intelligence in prostate histopathology: where are we in 2021? Curr Opin Urol. 2021 Jul 1;31(4):430–435. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000883. PMID: 33965977.

- Skrede OJ, De Raedt S, Kleppe A, Hveem TS, Liestøl K, Maddison J, Askautrud HA, Pradhan M, Nesheim JA, Albregtsen F, Farstad IN, Domingo E, Church DN, Nesbakken A, Shepherd NA, Tomlinson I, Kerr R, Novelli M, Kerr DJ, Danielsen HE. Deep learning for prediction of colorectal cancer outcome: a discovery and validation study. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):350–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140–6736(19)32998–8. PMID: 32007170.

- Ba W, Wang R, Yin G, Song Z, Zou J, Zhong C, Yang J, Yu G, Yang H, Zhang L, Li C. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning for melanocytic lesions using whole-slide pathological images. Transl Oncol. 2021 Sep;14(9):101161. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101161. Epub 2021 Jun 27. PMID: 34192650; PMCID: PMC8254118.

- Jaroensri R, Wulczyn E, Hegde N, Brown T, Flament-Auvigne I, Tan F, Cai Y, Nagpal K, Rakha EA, Dabbs DJ, Olson N, Wren JH, Thompson EE, Seetao E, Robinson C, Miao M, Beckers F, Corrado GS, Peng LH, Mermel CH, Liu Y, Steiner DF, Chen PC. Deep learning models for histologic grading of breast cancer and association with disease prognosis. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022 Oct 4;8(1):113. doi: 10.1038/s41523–022–00478-y. PMID: 36192400; PMCID: PMC9530224.